Life Inside a Microtubule

Microtubules (MTs) are dynamic cytoskeletal structures with multiple functions in cell growth, division, and morphological change. This review focuses on the MT lumen as a possible functional entity. The internal environment of the MT has its own peculiar biophysical state and is largely thought to be excluded from cytoplasmic influence, except for the 2 nm2 lateral pores1 and two 200 nm2 entrances at its ends2,3. Its biophysical state is outside the scope of this article, but it has very interesting vitreous, electromagnetic resonance, and optical properties4.

Several groups have expanded our view of what life is like inside MTs. The first of these breakthroughs came in the 1960s and 1970s by studying the structure of MTs at nm resolution with electron microscopy. Among other observations of MTs, researchers found evidence of 4-7 nm spherical particles in the lumen of MTs of highly fixed cells5-8. The particles’ existence and frequency varied between cell type, with neuronal cells having the most particles. Also, Burton9 found the particles could be voided from the lumen by rapid disassembly and re-assembly of intracellular MTs. Similar observations over the course of the next 30 years have culminated with observation of these particles in the MT lumen of non-fixed frozen sections of cells using vitreous cryoelectron microscopy or cryoelectron tomography10. Identification of intraluminal components has been difficult, but recent reports have found evidence of tubulin binding proteins and tubulin modifying enzymes.

Tubulin acetyltransferase (TAT) is known to transfer an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to the luminal side of stable MTs at Lys40 of alpha-tubulin1,11. Although it is thought that luminal acetylation does not influence MT stability, it has been associated with differential binding of MT-associated proteins (MAPs), kinesin motor affinity (involving MT surface binding site12,13, but this was recently disputed by two groups11,14), MT severing15, and increased MT stiffness which is useful in mechanosensory and cilia functions16,17. Whether the TATs and tubulin histone deacetylase enzymes (HDAC6 and Sirt2) are a component of the 4-7 nm particles described above remains to be determined. However, the single or dimer form of TAT could possibly fill the void (TAT is a 3 x 6 x 3 nm ovoid18) and there is evidence of MEC-17 (a C. elegans TAT homolog) being localized within the MT lumen and in close association with the inner MT wall16. Tau, a major neuronal MAP, is also known to have a binding site within the MT lumen19. In cilia and flagella organelles, binary microtubule structures are stabilized by microtubule inner proteins (MIPs) which transverse protofilaments and the A and B microtubule complexes27,28,29.

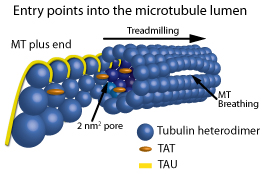

How do proteins and particles get into the MT lumen? There are the obvious entry points such as those mentioned in the first paragraph (2 nm2 pores and 200 nm2 ends). However, each have limitations, as the 2 nm2 pores’ access is limited to small molecules (<1000 Da20,21) or thin strand-like molecules; for the MT ends, access is limited by the distance molecules can travel by diffusion22. A MT’s mid-point can be upwards of 40 µm away from the MT end, and theoretical measurements put the diffusion rate of a 50 kDa protein entering an end between minutes/40 µm to years/40 µm, depending on the molecule’s affinity for internal MT walls22. Less obvious entry points include frayed MT ends10,23 and growing MT ends in conjunction with MT treadmilling24,25, and the breathing walls of the MT lattice recently observed by vitreous cryoelectron microscopy17 (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the entry points into the MT lumen. Showing, from left to right, a frayed/growing MT plus end capturing TAT and tau molecules, treadmilling, 2 nm2 pores, a 200 nm2 open MT plus end, and a breathing MT lattice.

Of the less obvious entry points, irregular or curling frayed MT ends have been observed in growing and shortening MTs in vitro, and recently in vivo via vitreous cryoelectron microscopy10 and digital model convoluted fluorescence microscopy23. When protofilaments are exposed at plus ends of MTs, the future MT lumen is exposed and possibly can act as a capture point for proteins/particles destined for the lumen. Subsequent treadmilling could allow the captured entities to move to the minus end of the MT at 1 to 60 µm/min25. This is one possible mechanism to explain why the MAP tau has a binding site in the lumen as well as on the surface of MTs when MTs are formed in the presence of tau, but not when tau is added to pre-formed MTs which only results in tau binding to the outside surface of MTs19. Thus, in practical experiments to show molecules captured inside growing MTs, molecules can be included in a reaction containing polymerizing tubulin as compared to using pre-formed MTs (for example, compare Cat. # BK029 versus Cat. # T240 datasheet method sections, see below).

In summary, several recent key papers indicate important molecules reside inside MTs, including acetylated alpha tubulin, MIPs, TATs, the major MT stabilizing agent (MSA) binding sites of taxol26, and of course, tau protein. In addition to the incredible biophysical properties recently reported by Sahu et al.4, these observations indicate life inside a MT is turning out to be just as interesting as on the MT surface.

Microtubule Related Research Tools

| Protein | Source | Purity | Cat. # | Amount | ||||

Microtubules | Bovine Brain | >99% | 4 x 500 µg | |||||

Microtubules | Porcine Brain | >99% | 4 x 500 µg | |||||

Tubulin Protein | Porcine Brain | >99% | 1 x 1 mg | |||||

| Tubulin Protein, MAP rich | Porcine Brain | 70% tubulin | 1 x 1 mg | |||||

| Tau Protein | Bovine Brain | >90% | 1 x 50 µg | |||||

| Microtubule Associated Protein (MAP) Fraction | Bovine Brain | >70% MAP2 | 1 x 100 µg | |||||

| Tubulin for HTS Applications | Porcine Brain | 97% | 1 x 4 mg | |||||

| Kit | Cat. # | Amount | ||||||

Microtubule / Tubulin In Vivo Assay Biochem Kit™ | BK038 | 30-100 assays | ||||||

Microtubule Binding Protein Spin-Down Assay Biochem Kit™ | BK029 | 30-100 assays | ||||||

Tubulin Polymerization Assay Biochem Kit™ | BK006P | 24-30 assays | ||||||

Tubulin Polymerization Assay Biochem Kit™ | BK004P | 24-30 assays | ||||||

Tubulin Polymerization Assay Biochem Kit™ | BK011P | 96 assays | ||||||

References

- Nogales et al. 1998. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature. 391, 199-203.

- Gonzales and Robbins. 1965. The homology of spindle and tubules and neurotubules in chick embryo retina. Protoplasma. 59, 377-391.

- Bassot and Martoja. 1966. Donnees histologiques at ultrastructurales sur les microtubules cytoplasmiques du canal ejaculateur des insects orthopteres. Z. Zelforsch. 74, 145-181.

- Sahu et al. 2013. Atomic water channel controlling remarkable properties of a single brain microtubule: Correlating single protein to its supramolecular assembly. Biosens. Bioelectron. 47, 141-148.

- Dustin. 1978. Microtubules. Spring-Verlag, Heidelberg. 33.

- Echandia et al. 1968. Dense core microtubules in neurons and gliocytes of the toad Bufo arenarum Hensel. Am. J. Anat. 122, 157-168.

- Peters et al. 1968. The small pyramidal neuron of the rat cerebral cortex. The axon hillock and initial segment. J. Cell. Biol. 39, 604-619.

- S;tanley et al. 1972. Fine structure of normal spermatid differentiation in Drosophila melanogastor. J. Ultrastruc. Res. 41, 433-466.

- Burton. 1984. Luminal material in microtubules of frog olfactory axons: Structure and distribution. J. Cell. Biol. 99, 520-528.

- Garvalov et al. 2006. Luminal particles within cellular microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 174, 759-765.

- Soppina et al. 2012. Luminal localization of alpha-tubulin K40 acetylation by cryo-EM analysis of Fab-labeled microtubules. PLoS ONE. 7, 1-9.

- Dompierre et al. 2007. Histone deacetylase 6 inhibition compensates for the transport deficit in Huntingdon’s disease by increasing tubulin acetylation. J. Neurosci. 27, 3571-3583.

- Reed et al. 2006. Microtubule acetylation promotes kinesin-1 binding and transport. Curr. Biol. 16, 2166-2172.

- Walter et al. 2012. Tubulin acetylation alone does not affect kinesin-1 velocity and run length in vitro. PLoS ONE 7:e42218. doi:10.1371 / journal.pone.0042218.

- Sudo and Bass. 2010. Acetylation of microtubules influences their sensitivity to severing by katanin in neurons and fibroblasts. J. Neurosci. 30, 7215-7226.

- Topalidou et al. 2012. Genetically separable functions of the MEC-17 tubulin acetyltransferase affect microtubule organization. Curr. Biol. 22, 1057-1065.

- Cueva et al. 2012. Posttranslational acetylation of alpha-tubulin constrains protofilament number in native microtubules. Curr. Biol. 22, 1066-1074.

- Kormendi et al. 2012. Crystal strucuture of tubulin acetyltransferase reveal a conserved catalytic core and the plasticity of the essential N terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41569-41575.

- Kar et al. 2003. Repeat motifs of tau bind to the insides of microtubules in the absence of taxol. EMBO J. 22, 70-77.

- Maccari et al. 2013. Free energy profile and kinetics studies of paclitaxel internalization from the outer to the inner wall of microtubules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 698-706.

- Ross and Fygenson. 2003. Mobility of taxol in microtubules bundles. Biophys. J. 84, 3959-3967.

- Odde. 1998. Diffusion inside microtubules. Eur. Biophys. J. 27, 514-520.

- Demchouk et al. 2011. Microtubule tip tracking and tip structures at the nanometer scale using digital fluorescence microscopy. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 4, 192-204.

- Hotani and Horio. 1988. Dynamics of microtubules visualized by darkfield microscopy: treadmilling and dynamic instability. Cell Motil. Cytoskel.(now Cytoskeleton). 10, 229–236.

- Waterman-Storer and Salmon. 1997. Microtubule dynamics: Treadmilling comes around again. Curr. Biol. 7, R369–R372.

- Field et al. 2013. The binding sites of microtubule-stabilizing agents. Chem. Biol. 20, 301-315.

- Sui H and Downing K. 2006. Molecular architecture of axonemal microtubule doublets revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Nature, 442, 475-485.

- Nicastro D. et al. 2006. The molecular architecture of axonemes revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science, 313, 944-948.

- Nicastro D. et al. 2011. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals conserved features of doublet microtubules in flagella. PNAS, www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.107/pnas.1106178108.