Key findings in this article

This article describes:

- Intracellular condensates and the actin cytoskeleton work in concert to alter the location and reaction kinetics of specific molecules.

- Provides specific examples of molecular condensation and their reconstitution in vitro.

- How conditions of cellular stress leads to molecular condensation

What are molecular condensates?

Biomolecular condensates are membraneless compartments that can assemble biomolecules and are often formed through processes like liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). These biomolecular organelles contribute to multiple biological processes and regulatory mechanisms(rev. in 1).

Why are biomolecular condensates important?

A growing body of evidence suggests that failures in the regulation of biomolecular condensates can lead to dysfunctional protein assemblies and may contribute to a range of pathological processes and diseases(rev. in 2, 3).

How does the cytoskeleton assist the function of condensates?

Several studiesshow how condensates appear to directly regulate or be regulated by the cytoskeleton(rev. in 4). For example, several microtubule-associated proteins have been shown to undergo LLPS, which results in the recruitment and nucleation of microtubules(rev. in 4). This newsletter highlights several recent findings showing how biomolecular condensates regulate actin-binding proteins, actin polymerization, and actin-dependent biological responses to cellular stress.

How are particular functions of the actin cytoskeleton regulated by condensates?

There is a growing body of evidence that LLPS condensates may add another layer of regulation to actin polymerization/depolymerization through the accumulation of key actin-binding proteins(rev. in 4). For example, the Vale lab determined that T-cell receptor signaling led to membrane-associated microclusters of signaling molecules that spontaneously separated into LLPS condensates, enhanced the activity of N-WASP and Arp 2/3, and promoted actin polymerization in vitro and in cells5. Similarly, phosphorylation of the nephrin transmembrane protein and the subsequent formation of Nephrin/Nck/N-WASP membrane-associated protein clusters led to phase separation and actin assembly in the presence of the actin nucleator, Arp 2/36,7. In another example, Weirich et al. described how the filamin ABP converted liquid-phase short actin filaments into spindle-shaped droplets in a density-dependent fashion, providing further evidence that ABP condensation can alter actin organization8. More recently, the nuclear localizing myosin phosphatase rho-interacting protein (MPRIP) utilized its C-terminal disordered region to form LLPS condensates that promoted nuclear F-actin fiber formation9. Interestingly, some condensate-driven F-actin polymerization has a built-in control checkpoint, which was elegantly studied in C. elegans oocytes, where N-WASP condensates initially triggered F-actin polymerization; however, once too much F-actin was present, N-WASP dissociated and the condensate dissolved10.

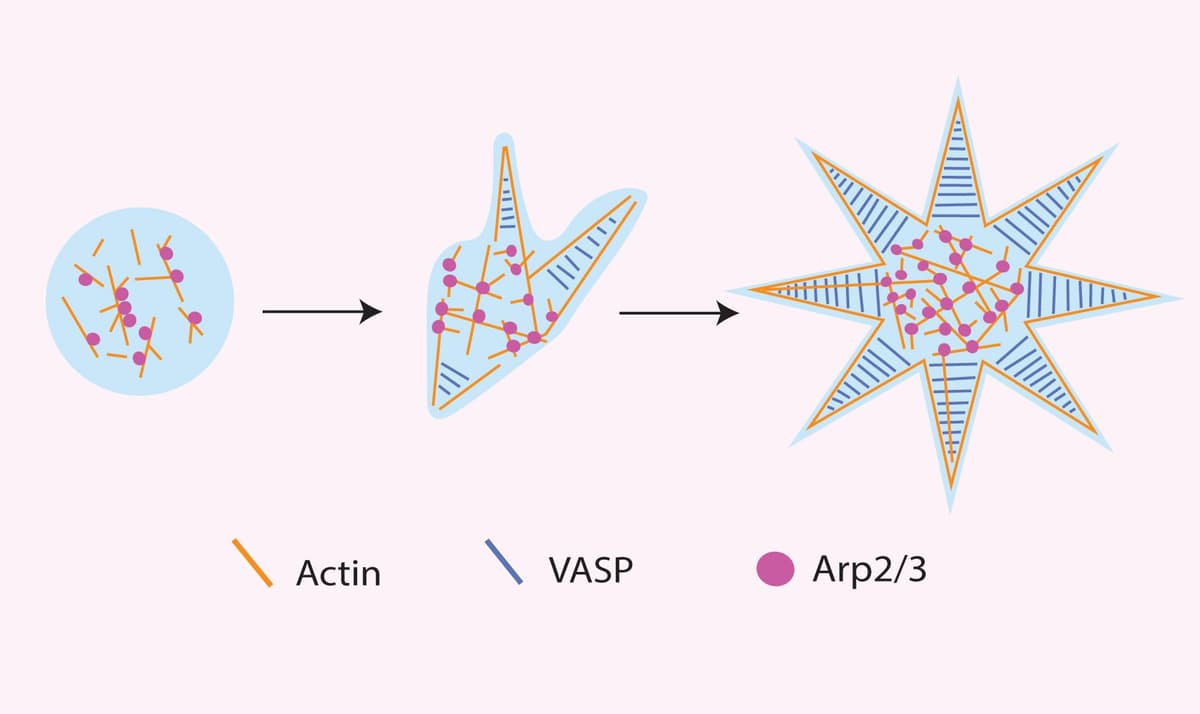

How specific is the regulation of actin polymerization in an LLPS?

There is clear evidence that condensates containing ABPs can promote actin polymerization; however, it was not known whether this increase was due to the concentrating effect of LLPS on ABPs or if condensates promote specific activities of discrete molecules that are activated to drive downstream outputs like actin assembly. The Rosen lab tested this through a detailed investigation of how the Nephrin/Nck/N-WASP complex activated Arp2/3 and actin polymerization11. They identified that the dwell times of N-WASP and Arp2/3 were limiting factors regulating actin polymerization, and dwell times of these proteins were higher in these molecular condensates relative to outside these clusters. Importantly, the dwell time of N-WASP was dependent on the stoichiometry of N-WASP to Nck and Nephrin rather than on the absolute density of N-WASP, suggesting that condensates promote specific activities of component molecules and are more than simple concentrating mechanisms. Another study sought to investigate this question regarding condensate function in a different way by asking how the presence of both an actin nucleating factor (Arp 2/3) and an actin bundling protein (VASP), which are present simultaneously throughout the cell, alters actin behavior in condensates. The group found that differing compositions of VASP and Arp 2/3 promoted distinct actin network morphologies and altered condensate formations12 (see figure 1). These findings suggest that condensates may have a profound effect on actin networks by compartmentalizing specific ABPs to temporally and spatially promote specific actin morphologies.

Can in vitro assays replicate the in vivo observations?

In 2023, Graham et al. identified VASP as an actin polymerizing and bundling protein that forms condensates in the presence of molecular crowding agents13.These VASP condensates promote actin polymerization that ultimately deforms the droplet into rod-like structures and may be an important mechanism for cellular architectures rich in parallel actin filaments. However, a study by Waizumi et al. showed that molecular crowders like PEG and dextran sufficiently drive F-actin enrichment in dextran-rich microdroplets14.Therefore, in a follow-up study, the Stachowiak group showed that condensates composed of VASP and its binding partner Lamellipodin sufficiently produced condensates in the absence of PEG and successfully promoted actin assembly15. Unexpectedly, they found that Lamellipodin alone, which binds actin but does not have polymerase activity, promoted actin polymerization in condensates15. This suggested to them that any protein that can bind actin and also form protein condensates has the potential to drive actin polymerization.They tested this hypothesis by creating a chimera of an F-actin-binding motif and a non-ABP condensate-forming protein, and found that this chimeric protein did form condensates that facilitated actin assembly15; an interesting finding that may broaden how actin polymerizing proteins are defined.

How do actin condensates respond to cell stress?

Cellular stress conditions, such as energy starvation and hyperosmotic stress, can lead to significant changes in cell morphology and metabolism. Cells remodel their actin cytoskeleton during stress conditions for several reasons, including reducing energy consumption and modifying cellular processes(reviewed in 16, 17). Growing evidence suggests that biomolecular condensates are a critical mechanism utilized by cells to respond to cellular stressors like reactive oxygen species, osmolarity, and nutrient changes(reviewed in 18, 19). Several researchers recently investigated whether cellular stressors utilize biomolecular condensates to regulate actin morphology in response to stress. Yang et al. report that hyperosmotic stress initially promotes actin severing, which leads to a tropomyosin 4 (TPM4) condensate formation20. More so, they found that the TPM4 condensates recruit glycolytic enzymes, are enriched with NADH and ATP, and undergo actin wetting (the process where condensates spread along actin filaments); ultimately, linking glycolytic sensing to cytoskeletal reorganization.In another study, researchers investigated the regulatory mechanisms by which actin cables remodel during energy starvation21. The group reported that Spa2 undergoes phase separation, actin wetting, and ADP-actin filament assembly upon energy starvation in yeast cells.Zhang et al. also investigated the role of actin in stress response and identified that the ABP diaphanous-related formin 3 (DIAPH3) acts as an actin nucleator that can initiate LLPS and form condensates as a mechanism to sequester DIAPH3 and prevent the assembly of F-actin in filipodia in response to stress22.

What are the future directions of actin and LLPS condensates?

The importance of biomolecular condensates is still emerging, yet the information above clearly shows that these membraneless compartments have a profound effect on ABPs and their ability to control actin polymerization and function. Seminal studies revealed how membrane receptor signaling drives condensate formation to facilitate actin assembly, but the recent studies deducing how cellular stressors also utilize these biomolecular condensates to control actin are fascinating as well. Outside the scope of this newsletter, but still very relevant, is the growing body of work that the actin cytoskeleton also affects cellular condensate formation; in fact, some studies have even investigated the reciprocal interplay between them4, 8, 23. Many of these LLPS/actin studies can be reconstituted in vitro using proteins obtained from Cytoskeleton, for more information click here.

References

6. Kim, S., et al., Phosphorylation of nephrin induces phase separated domains that move through actomyosin contraction. Mol Biol Cell, 2019. 30(24): p. 2996-3012.

7. Banjade, S. and M.K. Rosen, Phase transitions of multivalent proteins can promote clustering of membrane receptors. Elife, 2014. 3.

8. Weirich, K.L., et al., Liquid behavior of cross-linked actin bundles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(9): p. 2131-2136.

9. Balaban, C., et al., The F-Actin-Binding MPRIP Forms Phase-Separated Condensates and Associates with PI(4,5)P2 and Active RNA Polymerase II in the Cell Nucleus. Cells, 2021. 10(4).

10. Yan, V.T., et al., A condensate dynamic instability orchestrates actomyosin cortex activation. Nature, 2022. 609(7927): p. 597-604.

12. Graham, K., et al., Liquid-like condensates mediate competition between actin branching and bundling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2024. 121(3): p. e2309152121.

13. Graham, K., et al., Liquid-like VASP condensates drive actin polymerization and dynamic bundling. Nat Phys, 2023. 19(4): p. 574-585.

14. Waizumi, T., et al., Polymerization/depolymerization of actin cooperates with the morphology and stability of cell-sized droplets generated in a polymer solution under a depletion effect. J Chem Phys, 2021. 155(7): p. 075101.

15. Walker, C., et al., Liquid-like condensates that bind actin promote assembly and bundling of actin filaments. Dev Cell, 2025. 60(11): p. 1550-1567 e4.

16. Williams, T.D. and A. Rousseau, Actin dynamics in protein homeostasis. Biosci Rep, 2022. 42(9).

17. DeWane, G., A.M. Salvi, and K.A. DeMali, Fueling the cytoskeleton - links between cell metabolism and actin remodeling. J Cell Sci, 2021. 134(3).

18. Rabouille, C. and S. Alberti, Cell adaptation upon stress: the emerging role of membrane-less compartments. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2017. 47: p. 34-42.

19. Alberti, S. and A.A. Hyman, Biomolecular condensates at the nexus of cellular stress, protein aggregation disease and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021. 22(3): p. 196-213.

20. Yang, W., et al., TPM4 condensates glycolytic enzymes and facilitates actin reorganization under hyperosmotic stress. Cell Discov, 2024. 10(1): p. 120.

21. Ma, Q., et al., Spa2 remodels ADP-actin via molecular condensation under glucose starvation. Nat Commun, 2024. 15(1): p. 4491.

22. Zhang, K., et al., DIAPH3 condensates formed by liquid-liquid phase separation act as a regulatory hub for stress-induced actin cytoskeleton remodeling. Cell Rep, 2023. 42(1): p. 111986.

23. Feng, X., et al., Myosin 1D and the branched actin network control the condensation of p62 bodies. Cell Res, 2022. 32(7): p. 659-669.